“What role will creativity and play have in the future of arts education?”

As an art teacher and digital literacy coach, it is important to me to consider how art education might evolve in the future and what role technology might play. As I investigated the role of creativity, it became clear that the misconception of creativity as solely for the Arts is a common one. Rachel McGarrigal, suggested that this was true for her and that she “had been guilty of thinking that creativity was a synonym for the Arts”. She cited Anna Craft, saying “In the economic environment, the terms ‘entrepreneurship’ and ‘enterprise’ are used, whereas in sociology the term used is ‘innovation’. Yet in education and psychology, the term ‘creativity’ is widely used” (Craft, 2001). It is clear that this may be where the assumption arises that creativity and the arts are mutually exclusive.

Banaji and Burn’s article, “Rhetorics of Creativity” formed a springboard to many aspects of creativity theories and it was at this point that I had to decide which were most poignant to the future of art education in particular. Craft’s writings on possibility thinking and playfulness guided me in choosing avenues to explore in relation to the future of education. Whilst reading Banaji and Burn’s article, play seemed a common link throughout. In a conversation with Judith Kleine Staarman, it became clear how creativity and play are a fundamental aspect of learning and how influential Finland’s educational philosophies are becoming to the rest of the world. Recent articles in the media talk about the importance of “soft skills” (Ma, 2018) and this is reiterated by Krista Kiuru, Finland’s minister of education and science, regarding the importance of developing emotional intelligence, vocational courses and values beyond academics (Gross-Loh, 2014).

My presentation centred around the connection between possibility thinking and alternative futures for art in a digital context, citing recent reports on the necessity of creativity as a core skill and the works of both Craft and Inayatullah. I talked about how play and creativity are interconnected, and I will explore possible digital futures further. It is clear that despite an uncertain future, digital and media literacy is a necessary fluency. You only have to look at the rapidly advancing developments in the past 5-10 years to realise that it is even more important to prepare our students for this uncertainty by giving them the skills to creatively work through this change.

I wanted to explore what creativity meant to me and my school context, to examine how art education is changing and what it might look like in the future, looking at the possible discord or cohesion of traditional art education and the emergence of new technology.

I see many practices of creativity inherent in the arts, yet other subjects focus on knowledge and content, driven by exam requirements. So where is the time for creativity? But shouldn’t we be asking where can creativity be built in to the already existing curriculum, rather than as an add on?

Figure 1: Mindmap – What is Creativity by Nicki Hambleton

Figure 2: Menti poll What is creativity?

Looking at Figures 1 & 2, one can see creativity is not tied only to the Arts: problem-solving, divergent thinking, play and curiosity exist in all of us. Craft discusses that, since the shift to STEM, there is even more need to bring back creativity across the curriculum. Invention and innovation are at the heart of STEM and the Horizon report now supports STEAM to incorporate key aspects of the Arts to drive creativity (Horizon report, 2017). Craft and Jeffery make clear distinctions between “teaching creatively and teaching for creativity”, the latter impacting the development of this key skill rather than lessons becoming more entertaining (Jeffery & Craft, 2010).

John Dewey said that everyone is capable of being an artist. Often individuals regard artistry and creativity as a gift, or that you had to be born with it, but as Craft explains this assumption should apply to historical geniuses like da Vinci, Einstein and Mozart (known as Big C creativity). Conversely, little “c” creativity, relates to personal creativity and can be distinct from the Arts: a new idea or creation such as a poem or recipe. Ken Robinson reiterates this, discussing the imagination and “genius” of primary children (Robinson, 2006) and Craft reinforces the notion that everyday creativity is needed to cope with the rapidly changing society we live in. Conversely, Banaji and Burn explain that creativity often arises from “routine” just as your best ideas might arise during a shower or when dropping off to sleep. They reinforce the idea of ubiquitous creativity and that individuals who are not naturally creative may develop creative abilities and awareness through their engagement with arts projects and collaborations (Banaji & Burn, 2010).

Linking to the idea of working together in creative spaces, the rise of Makerspaces has ensured that more schools help students to engage in play and making for enjoyment or to pursue a passion independently. This spike in interest has resulted in new learning spaces like our “Ideas Hub” (Figure 3) bringing together art, design, technology, engineering and science for all ages and with innovation and play at the heart.

Figure 3: Idea Hacks, UWCSEA 2017

Virtual spaces, social media and games often incorporate play based elements. Understanding popular culture and the way youngsters communicate, interact and play today is relevant to affect change in our teaching content and style. Inayatullah’s future theories discuss moving away from a used future, where nothing really changes, towards alternative futures. To plan for an uncertain future, we need to help students to learn how to learn and become more independent and self-managed about the relevant skills to equip them for change and a diverse world. It is in this way of thinking that consideration can be given to “impossible futures”. Inayatullah et al talk about having a vision of the future rather than a set out road map. We need to consider unique possibilities “that change the direction of reality” (Bussey, Inayatullah, Milojevic, 2008). Some aspects of the future can be mapped based on current trends and developments in globalisation and technology advancements such as virtual reality and artificial intelligence, but it is about being open to a range of alternative futures and possibilities rather than a single one future ahead of us. At the heart of these alternative futures lies creativity. Creativity is as important in education as literacy, and we should treat it with the same status (Robinson, 2006). At the heart of creativity are play and experimentation.

In my presentation, I used Craft’s theory on probable, possible and preferable futures and possibility thinking to think about how the future of art might look. Probable futures for art may entail addressing digital futures, moving from traditional materials based lessons to a laptop or tablet. A possible future of art could see both formal and emerging art forms taught to complement each other and a preferable future might be a seamless integration of technology alongside traditional skills with personal choice at the centre of learning. This view of art may not be every art educators ideal, yet we must move the curriculum forward to ensure art is not pushed out as a subject and that it remains relevant in a future digital world. Whatever the future of art education, play must still form a central part.

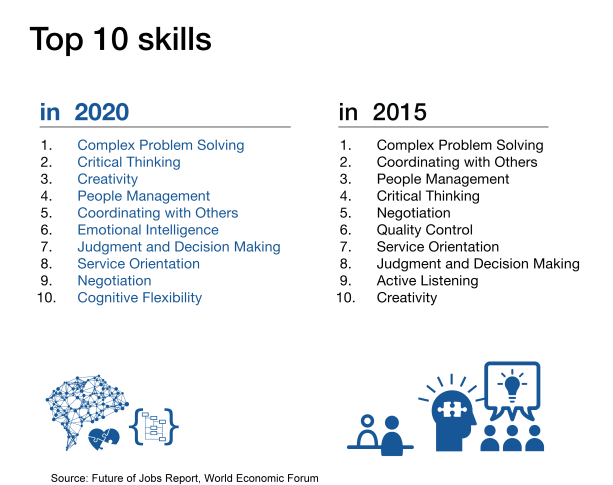

Figure 4: The Future of Jobs (WEF, 2016)

Howard Gardner said that “an intelligence entails the ability to solve problems or fashion products that are of consequence in a particular cultural setting or community” (Gardner, n.d) and that intelligences involve various amounts of human endeavour. Everyone, he says, possesses these intelligences or “abilities, talents or mental skills” in varying degrees. He describes examples of these intelligences as writing a story or playing chess and the same could be applied to the arts and creativity. This is particularly true in regard to problem-solving “from scientific theories to musical compositions to successful political campaigns” (Gardner, 1993). As reported in the Future of Jobs, complex problem solving remains the top skill required now and in the future (Figure 4) and goes hand in hand with creativity when regarding issues of overpopulation, conflict and climate change. Csikszentmihalyi states categorically that “there is no question that the human species could not survive if creativity were to run dry”. He equates the future to survival and that developing new solutions will be dependent on creativity. Ironically these modern and future problems were brought about by our own ingenuity and “yesterday’s creative solutions” (Csikszentmihalyi, 1996).

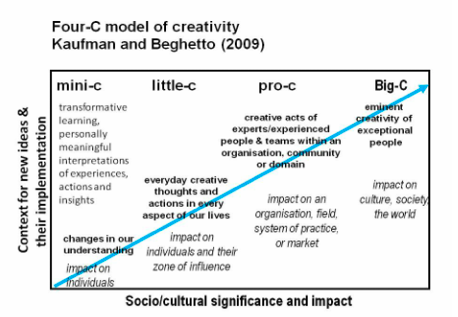

As we lead increasingly technology-driven lives, we need to become more self-directed. Craft describes this personal agency as “little-c creativity”. In Figure 5 below, we see the increasing impact the 4 forms of creativity have on others and specifically where this relates, with little-c, to aspects of our daily lives. Craft explains how important little-c is in coping with change and dealing with small levels of creative problem solving (Craft, 2005).

Figure 5: Four-C model of creativity, Kaufman & Beghetto, 2009

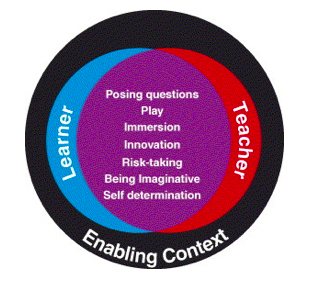

Craft describes possibility thinking as “the engine that drives little-c creativity” and Burnard’s diagram (Figure 6) describes key features of PT to include innovation, imagination and play. It is interesting to note the mirroring language with the poll on “What is Creativity” in Figure 2.

Figure 6: Possibility Thinking (Burnard, 2006)

Reading Craft’s thoughts on play and playfulness to engage and foster creativity draws me back to my classroom practice and the nature of experimentation in art. Risk taking is inherent in teenagers whether through gaming or sports, yet this free-play or abandonment of childhood often dissipates the older they get. With this in mind, I would like to focus on aspects of ubiquitous creativity and the connection between play and creativity.

Craft discusses at length how Possibility Thinking is used as a lens for understanding creativity, specifically in the early years’ context. She describes “What is” to “what might be” and through this shift “PT might include questioning, imagination and play” (Craft, Chappell, Cremin and Jeffrey, 2015). This process of inquiry and inquisitiveness, natural in young learners must also be continued as they progress through school and into adult life. Creativity has been noted as a fundamental skill for the future of education alongside critical thinking and problem-solving. These 3 interconnected skills are the foundation of art and design education and the inclusion of these are relevant throughout the curriculum.

Margaret Boden states that exploration is the start of creativity: by exploring an idea, many possibilities spring up and this in itself is creative. Because of this, one can surmise that creativity has a lot in common with play, often “open-ended with no particular goal or aim” (Boden, 2004). Exploring within one’s mind, she describes as “mental maps”. This conscious and subconscious thinking is not related solely to one curriculum area and mind maps are commonplace across learning contexts. As with scientific and computational thinking or decision making, a journey must occur to solve a problem or explore solutions. When facing unknown futures and possibilities, being conscious of how a future can be mapped out can help embrace change.

With technology changing rapidly, education institutions need to be able to explore many ways it can enhance learning. Generation Z are more adept at trying out new things. Just as they might explore a new game or app, they learn by trying, failing, trying again. Boden describes creativity as “playing around”, just as a child plays with a string of beads or a pile of lego to make something new. Play in the young is a natural process to learn about the world and its possibilities. But as we get older, even by early teens, this ability to play freely is diminishing. However, according to Boden, playing is a way of “comparing one way of thinking with another, mapping one onto the other” just as one does with Maths or Science (Boden, 2004). Craft reinforces the idea of play and creativity, relating possibility thinking and the use of technology to amalgamate the actual and online spaces our students learn in.

At the centre of research into the benefits of play is the Playful Learning Center, Helsinki. In Finland, play forms a large part of the students’ day. Kristiina Kumpulainen, talks about playful learning as “an attitude to life” and explains how important the nature of creativity is when one makes something not imagined before. The most effective way to engage others in this experience is to listen and join in, just as one would as a parent with your child and this philosophy can be applied in the classroom with the adult learning alongside a child- to play together to learn together (Kumpulainen, 2016).

Listening to the ideas of Kumpulainen and the nature of learning and play helped me to see a possible future for collaborative learning in art. Watching my Middle School students play with new sculptural materials and ideas, learning together, reminded me of how their social worlds are built on communication and connections.

Elliot Eisner believed that studying the Arts helped develop the holistic child and that part of this theory included critical understanding and thinking skills, amongst others. He talks about the relevance of artistic endeavour to all aspects of the curriculum. Often schools focus on achievement and academic success rather than building on inquiry. Herbert Read describes the process of “being artistic’ not as a practice only by artists but that the creation of work from ideas, imagination and thinking is relevant to any discipline. Therefore this approach should be clear across education and relevant to professions as wide afield as mathematicians, engineers or surgeons. Similarly, Craft says, in order to foster creativity, classrooms should allow for “mistakes and encourage experimentation, openness and risk-taking” (Craft, Chappell et al, 2015) and these are skills for life.

Figure 7: “Shear” by Bugdanoglu, 2016)

Returning to the future of art education draws me back to the amalgamation of the traditional and digital worlds. In my video, the interactive work of Bugdanoglu exemplifies the new directions artists are exploring by playing with and combining media for the audience to literally play with. At Art Stage, art can be seen to explore and represent new possibilities of the future, capturing previously unthought of ideas and visions. It also brings together the actual and the virtual using technology to change our perception of the world. The future of art education must embrace technological advancements yet be true to its roots. In the presentation, I wanted to demonstrate how immersive art can be as an experience, the connection and symbiosis between artist and audience.

Figure 8: Photos taken by Nicki Hambleton at The Art Science Museum, Singapore 2016

Modern exhibitions demonstrate possible futures of art with audiences interacting with the creations. Singapore Art Science Museum brings together STEAM and a truly immersive experience (Figure 8). By interacting, you become part of the art. Similarly, a recent exhibition, Mirages et Miracles, shows the potential of AR to connect the artist and audience through a unique experience. It is exciting and challenging to imagine teaching and learning in this way. Innovation and risk-taking are embedded in possibility thinking and it is through questioning and exploring alternative futures that a relevant curriculum can be imagined. Of course, along with great innovation comes challenges. As Laura Cotterill pointed out in her feedback, “how can we keep up with such transitions in terms of educator’s knowledge and experiences with alternative forms of digital engagement tools?” This indeed is an issue for many schools, how do they chose which avenue to explore, which media to invest time, money and resources in and when and how do educators become proficient in these new skills?

Figure 9: Mirages et Miracles https://www.am-cb.net/projets

Robinson recognised that schools need to ensure subjects are useful for work. As the skills required for existing jobs change, schools need to place more value on creativity: creativity to develop a changing workforce that will be needed in the future to develop innovative solutions far more relevant than academic success. Creativity is no longer only for the young or artistic. Mitch Resnick reinforces Robinson’s reflection on the importance of this fundamental skill for the future workforce, suggesting that adults and children alike should focus more on “imagining, creating, playing, sharing, and reflecting, just as children do in traditional kindergartens” (Resnick, 2017). Robinson urges us to use our “gift of human imagination” and to build on this capacity in our students “to educate their whole being so they can face this future” (Robinson, 2006).

References

Art Stage. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.artstage.com/singapore/pages/9/event

Banaji, S. (n.d.). Mapping the rhetorics of creativity. The Routledge International Handbook of Creative Learning. doi:10.4324/9780203817568.ch4

Beghetto, R. A., & Kaufman, J. C. (2007, 05). Toward a broader conception of creativity: A case for “mini-c” creativity. Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts, 1(2), 73-79. doi:10.1037/1931-3896.1.2.73

Berkay Bugdan | Art & Design. (n.d.). Retrieved from http://berkaybugdan.com/

Boden, M. A. (2005). The creative mind: Myths and mechanisms. Routledge.

Bussey, M., Inayatullah, S., Milojevic, I. (2008). Alternative Educational Futures: Pedagogies for Emergent Worlds

Chappell, K., Walsh, C., Wren, H., Kenny, K., Schmoelz, A., & Stouraitis, E. (2017, 10). Wise Humanising Creativity. International Journal of Game-Based Learning, 7(4), 50-72. doi:10.4018/ijgbl.2017100103

Craft, A (2001). Analysis of Creativity Literature

Craft, A. (2011). Creativity and education futures: Learning in a digital age. Trentham.

Craft, A., Chappell, K., Cremin, T., & Jeffrey, B. (2015). Creativity, education and society. Institute of Education Press, University College.

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2015). Creativity: The psychology of discovery and invention. Harper Perennial Modern Classics.

Feldman, D. H., Mihály, C., & Gardner, H. (1994). Changing the world: A framework for the study of creativity. Praeger.

Future of Jobs (2016) Retrieved from http://reports.weforum.org/future-of-jobs-2016/

Gardiner, H (1993) Multiple Intelligences: In a Nutshell retrieved from http://www.pz.harvard.edu/resources/multiple-intelligences-in-a-nutshell

Gross-Loh, C. (2014, March 17). Finnish Education Chief: ‘We Created a School System Based on Equality’. Retrieved from https://www.theatlantic.com/education/archive/2014/03/finnish-education-chief-we-created-a-school-system-based-on-equality/284427/

Gross-Loh, C. (2014, March 17). Finnish Education Chief: ‘We Created a School System Based on Equality’. Retrieved from https://www.theatlantic.com/education/archive/2014/03/finnish-education-chief-we-created-a-school-system-based-on-equality/284427/

Home. (n.d.). Retrieved from http://plchelsinki.fi/

Homepage | Project Zero. (n.d.). Retrieved from http://www.pz.harvard.edu/

Jeffery, B & Craft, A. (2004, 03). Teaching creatively and teaching for creativity: Distinctions and relationships. Educational Studies, 30(1), 77-87. doi:10.1080/0305569032000159750

Ma, J: Everything we teach should be different from machines. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LH-fdIkdL_Q

Mirages et miracles – trailer. Retrieved from https://vimeo.com/248983439

Playful learning. (n.d) Retrieved from https://vimeo.com/147461730

Resnick, M., & Robinson, K. (2017). Lifelong kindergarten: Cultivating creativity through projects, passion, peers, and play. The MIT Press.

Robinson, K. (2006). Do schools kill creativity? Retrieved from https://www.ted.com/talks/ken_robinson_says_schools_kill_creativity

Walker, T. D. (2015, October 01). The Joyful, Illiterate Kindergartners of Finland. Retrieved from https://www.theatlantic.com/education/archive/2015/10/the-joyful-illiterate-kindergartners-of-finland/408325/

Walsh, C., Chappell, K., & Craft, A. (2017, 06). A co-creativity theoretical framework to foster and evaluate the presence of wise humanising creativity in virtual learning environments (VLEs). Thinking Skills and Creativity, 24, 228-241. doi:10.1016/j.tsc.2017.01.001

What can education learn from the arts about the practice of education? (n.d.). Retrieved from http://www.infed.org/biblio/eisner_arts_and_the_practice_of_education.htm